Conductive Flesh, From the Bite of a Leaky Carrier

Strat Coffman

In a story recounted many times, my grandmother swore she was hit by lightning. Not out in the familiar danger zones, like a cornfield or a public pool, but in her childhood house in Missouri, sitting in the kitchen with a toaster in a storm. She insisted that the aerial current hit the house, ran through its branching circuits, and jumped from the toaster into her. This house, like most built-in rural America in the 19th century, had exposed wiring. Lines of braided cord, held in place by white porcelain insulators, electrified the house. Without earthing wires to direct excess charges into the ground, static electricity could accumulate, giving off surplus energy via minor shocks and the occasional house fire. The house was leaky, activated.

For years after this incident, every time a storm approached, my grandmother would make rounds through all the rooms of the house, unplugging appliances, trying to disconnect the house from unwanted erratic forces and protect herself from the house. Meanwhile, the electrical industry continued its effort to insulate human bodies from surplus energy through internal wiring and other safety measures. In 1913, the National Electrical Code mandated that all electrical services in residential construction be grounded.1

Even though our modern management of electrical supply would have us believe that electricity is containable and discrete, our world—and our bodies—are threaded through with electrical activity. Unlike the on/off switch of a hard-wired supply, the body exhibits a range of receptivity and resistance to electrical current, modulated by factors like sweat gland activity and skin temperature. Living beings depend on electrical signals to coordinate internal functioning, distributing incantations of pulses that summon action and mood. Dermal tissue is conductive because it is composed of water and charged particles (ions). We are skin bags of salty liquid, charge ports giving off heat while humming at –3 to –7 volts. Our bodies, and any living bodies, have a talent for receiving electrical shock. We are sluts for energetic flows.

Around the time my grandmother was struck by lightning via her toaster, two brothers in New Zealand channeled live electrical current to shock another conductive body. The horse on their farm had a habit of rubbing up against their prized Essex car, bending its fenders and roughening its finish. The brothers rigged the ignition trembler coil set to electrify the car’s body when bumped. After this, as the story goes, car and horse never touched again. Swapping out the metallic auto sinew for circuits of wire, the brothers adapted this ad hoc setup into a containment device: the electric fence.

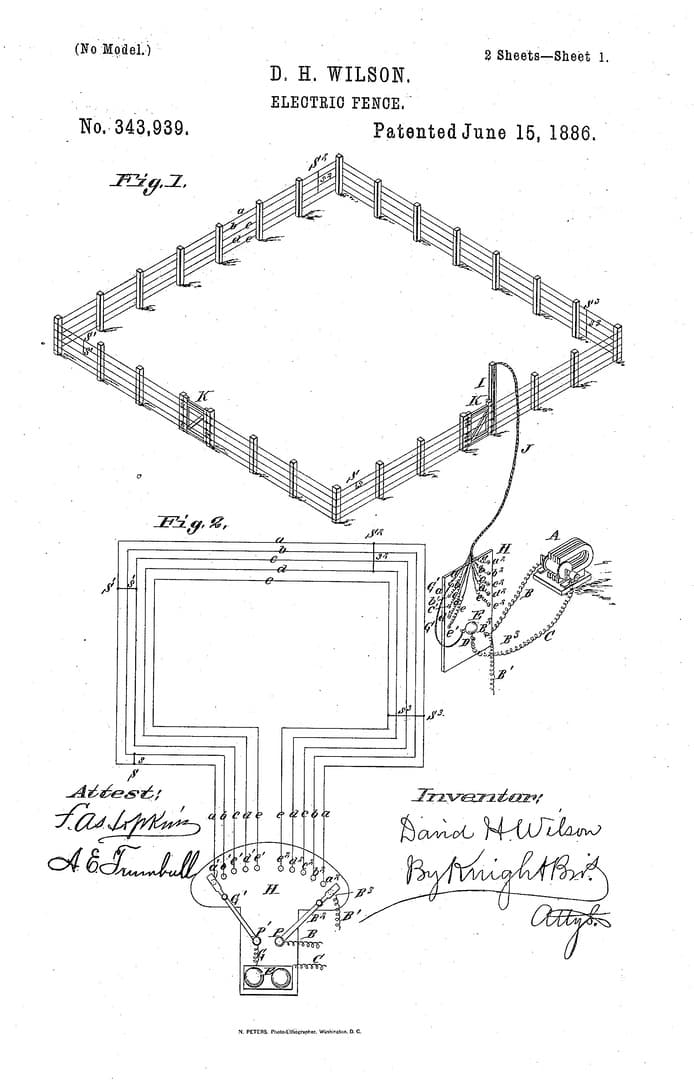

US Patent 343939, "Electric Fence," D.H. Wilson, 1886.

The electric fence has found wide use to contain livestock, for corralling and grazing management, but also in other areas for forcibly confining human bodies. It works, at least initially, because of the body’s vulnerability to electrical shock when it contacts the current. But soon after, as repeated exposure trains the contained bodies to stay away, actual shock is no longer necessary to prevent crossing. The boundary now lives in muscle memory. The electric fence can be physically spare, delicate even. In spools of wire or netting meandering through an expanse, live emission is condensed along a line.

As my grandmother, and others growing up in her time, came to see a house as an unreliable carrier, spilling excess charge, these inventions directed and harnessed the live current, containing the ambient risk haunting electrical systems. The fence locates where shock will occur, it creates a provisional territory. It also rationalizes the potency of the shock into another parameter tweaked by the twist of a voltage dial. It makes sensate—in the wild contortions of a jolted body—the abstraction of a property line or an agricultural zone, even when it cannot be seen.

Graphic for domestic dog fence product.

Maybe more familiar to many is the diminutive version of the dog fence, a buried wire that radiates a weak radio signal detected by a collar that shocks the pet wearing it. In the hotly territorial New England suburbs where I grew up, with property disputes dating back to colonial settlement, many families installed electric fences around their yard perimeters to keep their dogs from overstepping and sparking a feud anew. Advertised as “invisible” and “virtually anywhere,” these tasteful (aka discrete) backend disciplining services didn’t disturb the quaint neo-settler ambiance of the neighborhood, silently and continuously awake, shocking pets autonomously, while their owners ran to the grocery store or a yoga class. Unlike the exposed agricultural fence that indiscriminately zaps any body it touches, the dog fence is targeted. Only the dog wearing the collar will feel the bite of the fence paired with it. It is visually obscured but also operationally tidy, enacting a one-to-one fit between enclosure and body.

Sometimes as a kid, watching a dog do its thing in a front yard, I’d try to picture what it would look like, what wrenching jumps I’d witness, if the dog were to graze the undetectable boundary. Circulating in this was a desire to know the feeling myself, to force out of hiding the latent violence running through the backyard. I have a vague muscle memory from childhood of nudging the prong of a device while plugging it in and getting heavily shocked. I low-key loved the fleshy smudge, the forced release of muscle control. The way it dilated the moment. It felt instant and unending. A super micro release.

Sunbeam Deluxe Automatic Radiant Control toaster advertisement, circa 1950.

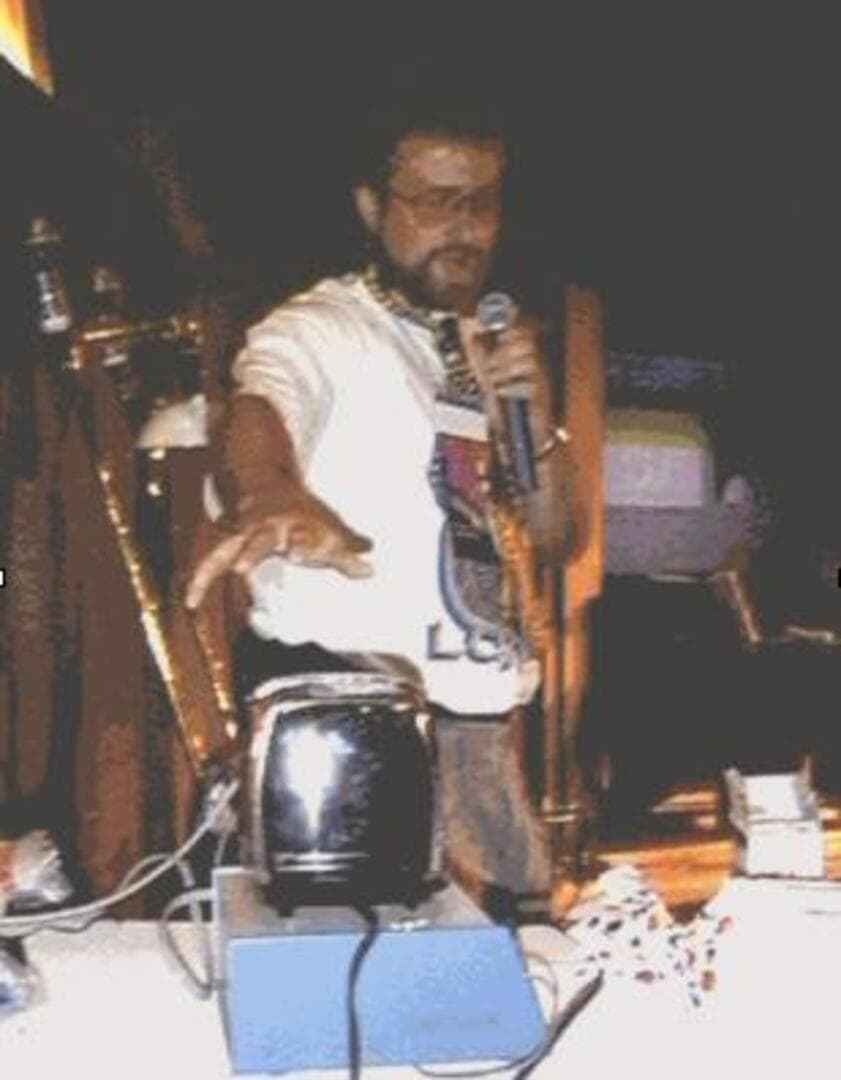

As electric shock gets deployed more severely and precisely, further corners of the domestic territory are being electrified. Every conceivable household item can now be hooked up to the internet. Mirrors, trash cans, forks. The first electrified “smart” thing was a toaster, specifically the Sunbeam Deluxe Automatic Radiant Control toaster, a 1949 model with a cult following. My other grandmother had one, which I used until its famed automatic lowering and lifting mechanism stopped working a few years ago. It had a stout body whose chrome casing got so hot it would burn your hand instantly. In 1990 a couple engineers in the United States connected one of these toasters to a clunky computer to make toast remotely. Because the toaster was already semi-automated, all they had to do was write a script that activated and deactivated the toaster’s power source. A photo from the demo at Interop, the electronics trade show where it debuted, shows the toaster sitting atop the computer brick, cords winding this way and that. The presenter’s hand is raised above it, as if summoning the apparatus into sentience. Meanwhile at a booth nearby another conference attendee was busy prompting a robotic dog to bark.

Demo of internet-connected toaster, Interop, 1990.

The human hand in this photo, standing in for the sorcery of the engineer, is increasingly ghosted, as the nexus of control migrates to a chip or dissipates altogether into a computing network. Meanwhile, the hand of the user, the flesh conduit, is opened up for finer meddling. In Disney’s 1999 millennial classic Smart House, a family takes a tour of their future home. In a kind of techno greeting with this personified domicile, this mommy house, the eager child places their hand on a glowing green interface. It hums as the light caresses their palm up and down. The handshake is punctuated by a loud tick and the child jerks their hand away, exclaiming, “You didn’t tell me that thing was going to bite me.” As the aggressively upbeat tour guide explains, the bite is a benign one. That’s just “her way of getting to know you,” she says, as the glitchy boss-mom voice of the house reads off the child’s biomedical profile. The ungovernable zap from my grandmother’s toaster gives way to the instant, and continuous, capture of biometric material, a body tax.

Still from "Smart House," 1999.

The more things get smart, the more power a house demands. The house of the pre-grounding era was erratic and almost animate, creaking in the elements, zapping its inhabitants here and there. Its risks to the body grew from the quirks of weather systems and faulty construction. In the contemporary smart house, the patron saints of tech do their best to exorcize the ghost from the machine. Encrypted whispers among sensors locked within the proprietary closure of the operating software. The vision sold by the swarm of Google’s Nest products is an inversion of the intuitions governing my grandmother’s childhood house: an electrified house is a secure house. It achieves its animacy through autonomous protocols authorized by the terms of use written by commercial parties. But in this transference, gaps persist, systems get hacked, and the body remains conductive.

Footnotes

-

The Electric Power Research Institute, “History of Residential Grounding,” https://www.epri.com/research/products/1005490. ↩