Send In the Clowns

Michael Snyder

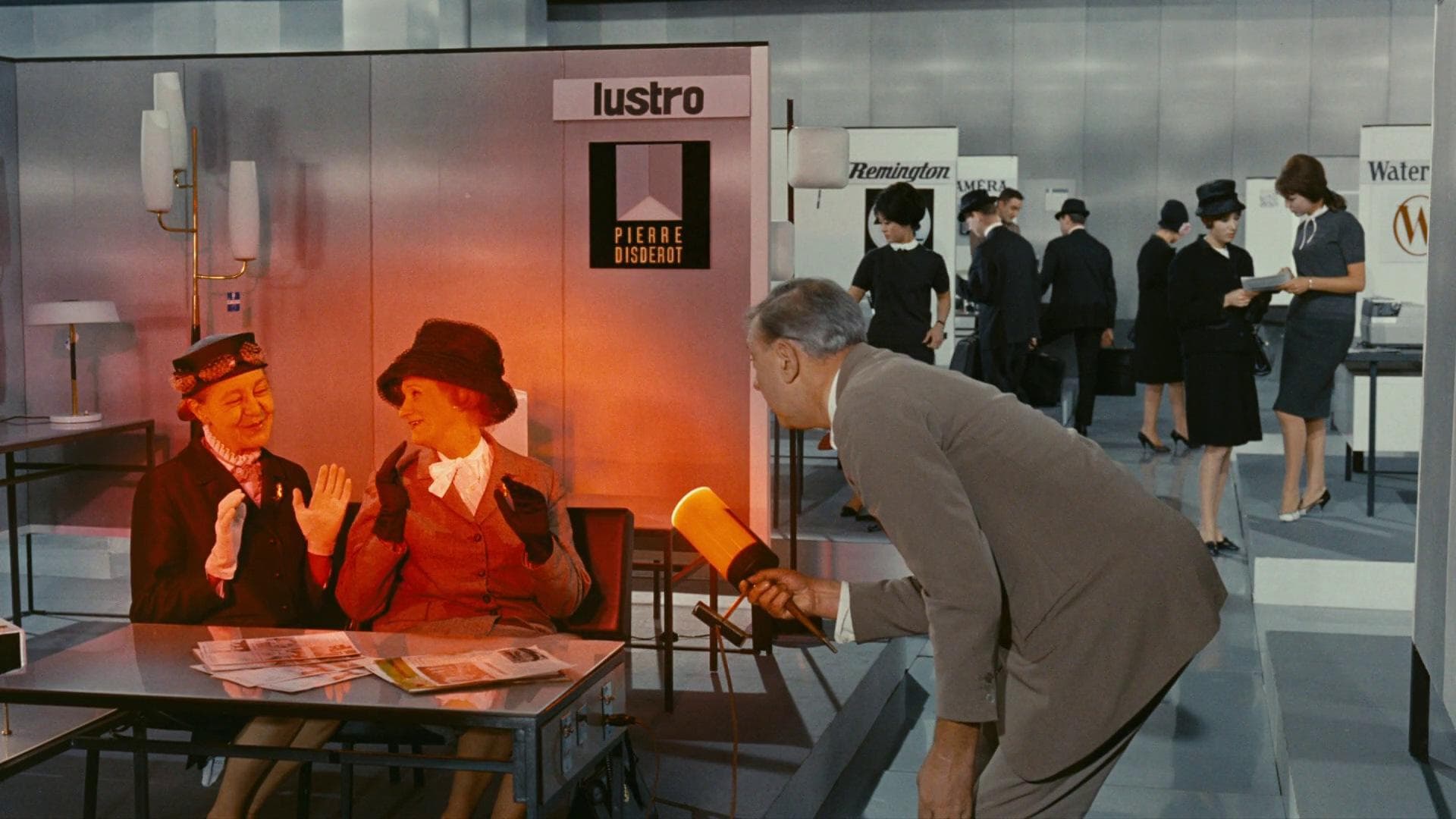

Early on in Jacques Tati’s 1967 masterpiece, Playtime, a befuddled Monsieur Hulot, played with shuffling charm by the director himself, wanders through a showroom of modern appliances. The showroom occupies the ground floor of a Miesian office tower in a mysterious, featureless city called Paris, whose more famous landmarks—the Eiffel Tower! the Arc de Triomphe! Sacre Ceour!—appear intermittently as impossible reflections in polished glass doors. Inside the showroom, interchangeable men and women muttering in German and English and even, occasionally, French, scurry through a grid of stalls that somehow, for all its orthogonal logic, becomes a maze. You can find your way around easily enough, but there appears to be no way out. Which is how Monsieur Hulot, our loveable luddite lost, ends up tasked with fixing a lamp by a pair of English women who mistake him for a clerk. When, moments later, he stumbles back into their presence (he’s done nothing to repair the lamp, of course) he fumbles for its plug at the end of a long wire and attaches it—a discomfiting flash of red; the women coo with pleasure—to an outlet embedded in the side of a table. And there, lo, 57 years ago, un accesorio espacial.

Still from Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati.

As an exhibition, Accesorios Espaciales reflects on the most basic elements of our built environment—the light switches, plugs and cords that we typically hide from view even as they facilitate just about every aspect of our day-to-day lives. But APRDELESP, as a firm, often begins its work from an exploration of typologies, and the show you’re seeing today began as an investigation not of accessories but rather of the showroom as a defining architectural space in contemporary life.

The showroom sequence occupies just 15 minutes of Playtime’s two-hour run, but it’s of a piece with the rest of Tati’s sweetly smirking satire of a thoughtlessly homogenized Modernity. In the opening sequence, Monsieur Hulot stumbles through an office building (or is it an airport?), descending an escalator over a cluster of cubicles that occupy another rigid grid; here, rather than vacuum cleaners with headlights or doors that slam “in Golden Silence,” the product on sale is productivity itself. The fish-bowl apartment block, where Monsieur Hulot gets trapped in a domestic dumbshow, puts at least four different ‘modern’ lives on backlit display for a bustling city street outside. In the 45-minute set piece that brings the movie to its nervous breakdown of a conclusion, a nightclub becomes a fluid showroom for high glam and bad behavior, where people start having fun only once they break away from their strictly rectangular table tops and stop scrutinizing one another—all of which happens as the slick, Modern stage-set that surrounds them quite literally comes crashing down.

Travel, Work, Commerce, Domesticity, Entertainment—in Tati’s delirious two-hour ballet of Modern alienation, all are essentially interchangeable, contained within the same glass boxes and wired for the same modern (in)conveniences. In this electrified, electrifying word, Tati suggests, everyplace is a showroom.

Showrooms as we know them today more or less came into existence at the tail end of the 19th century when the industrial revolution brought about rapid urbanization while facilitating the mechanized production of consumer goods. In her book Luxury and Modernism, the scholar Robin Schuldenfrei dedicates an entire chapter to a pair of early showrooms designed, beginning in 1910, by the celebrated industrial architect Peter Behrens working for the German company aeg, the Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft, or General Electric Company. Though aeg had previously maintained a ‘permanent showroom’ in its administrative offices, Behrens’ plush yet minimalistic display spaces “were both salesrooms and places of exhibition,” Schuldenfrei writes, “austere gems that instantly conveyed the coveted, luxurious nature of the goods sold within.” Compared to the clutter of readily available stuff packed into the windows of run-of-the-mill shops, Behrens’ aeg showrooms were sleek and alluring, imbuing electric kettles and floor fans with an aura of progress. Behrens’ showrooms instilled in Berlin’s wealthiest denizens what commentators at the time described as “Kauflust,” Schuldenfrei writes, “literally ‘buying desire.’”

In the United States, high-end furniture manufacturers opened private showrooms in the 1930s to sell their product lines directly to design professionals, banking on wholesale to float their businesses during the Depression. Open showrooms didn’t become common until the 1950s, a development that interior designers resented, fearing that they themselves might lose their sheen of exclusivity and that the well-trained floor staff—a key element of the showroom typology—might ultimately supplant them. Again, typical shops and even department stores offered a dense concentration of ready-to-buy products, while showrooms were characterized by the creation of an atmosphere. A store responded to an immediate need; a showroom created—and then satisfied—a future desire.

In the convoluted hierarchies of 20th-century capitalism, it was that very paucity of product that connoted, and still connotes, luxury. Consider: Herman Miller has showrooms; Crate & Barrel is a store. Ikea has lent a credible veneer of style to its big box warehouses by attaching them to showrooms filled with 1:1 dioramas of chipper Scandi practicality. A new car dealership is a showroom par excellence; a used car dealership, where you drive your purchase off the lot, is not. In the first season of the British sitcom Absolutely Fabulous, when Jennifer Saunders’ character, Edina Monsoon, wants to knock a haughty gallerina down a notch, she tells her, “You only work in a shop, you know, you can drop the attitude.” For many gallerists, who might wrinkle their noses at the suggestion that they work in retail at all, ‘you work in a showroom’ would have been insult enough. It would also have been entirely true.

But while showrooms rank high in the hierarchy of retail spaces, they’re still, well, retail spaces, which places them low on the prestige-ladder of architectural design—far below private homes and lightyears away from museums or places of worship or public housing. Where the perception of scarcity lends esteem to a product and the space that sells it, architecture has historically assigned value through permanence. Walls, at least the load-bearing kind, don’t move; a rooftop marks the difference between an indeterminate cluster of columns (is it art? a ruin?) and an easily identified marquis or pavilion. Most architects design from the outside in, beginning with walls and roofs, volume and mass (more poetic practitioners might talk reverently about narrative and light), eventually reaching interiors where the lead designer, or someone in her office, will suggest fixtures and, finally, maybe, a handful of furnishings. The objects the client already owns—save for art, which we tend to perceive as permanent in a metaphysical sense—rarely figure in the process at all. Products, things, the stuff sold in shops and showrooms alike, are, for the most part, infinitely mobile.

Light switches, electrical outlets and all the prefabricated accessories that make life livable occupy an even lower rung of this architectural hierarchy—throwaway necessities usually chosen, above all, for their discretion. Which is, it’s worth noting, pretty strange. Not so long ago, light switches seemed like magic, a point of contact between us and what art historian Dr. Sandy Isenstadt describes in his book Electric Light: An Architectural History as “the technological sublime.” Well into the 20th century many feared and thrilled to the idea of wiring their homes. “Projecting one’s will across space and bidding an otherwise invisible energy into material presence,” Isenstadt writes, “rehearsed a mythic moment of creation and echoed something of the divine.”

Early feminists lauded the light switch as a pathway to emancipation, allowing domestic workers to complete housework with a single, effortless gesture. In the United States, the spread of a national electrical grid in the 1920s and 30s seemed less an effect than a cause of national unity. In the dizzy optimism that followed World War II, the evolution of electrical appliances became a generative force behind the rise of corporate-Modern skyscrapers not unlike the one you’re standing in right now. Structural steel made it possible to build up in the late 19th century (around the time, not coincidentally, that Edison invents the lightbulb), but cool, fluorescent lights opened the door to economically viable buildings with deep, continuous floorplates free from the constraints of natural light. Cass Gilbert, the designer of New York’s Woolworth Building, which held the title of world’s tallest from 1913 until 1930, once described skyscrapers as “machines to make the land pay.” Isenstadt, meanwhile, describes the lowly switch in similar terms: “an engine of spatial commodification,” he writes, “by which a space was made modern.” A syllogism: Modernity is achieved through electrification. Electrification commodifies everything it touches. To be Modern is to be a commodity.

It didn’t take long for that essential capitalist logic to extend beyond buildings to encompass time and people themselves. James Thurber, in a 1933 essay in The New Yorker, makes light of his grandmother’s late-in-life terror that electricity “leaked […] out of empty sockets if the wall switch had been left on.” And while electricity does not, of course, “leak” in any literal sense, she was not, in more abstract terms, far off at all: electricity did seep into every aspect of our lives. It pushed working hours well past the edges of daylight (with smart phones, past any boundaries whatsoever) and, rather than emancipating women, piled on ever more absurd expectations as to just how much they might reasonably accomplish in a day. Tati knew this, too: See, Mon Oncle, the Monsieur Hulot film that preceded Playtime by nine years, in which a housewife spends what appears to be her entire day tinkering with machines and polishing sleek chrome surfaces, face washed with a beatific benzo-grin.

Today, the showroom and the electrical apparatus—commerce and energy—are, for better and very much for worse, defining features of our contemporary condition, so mundane as to be almost unseemly. Stores now want you to believe they’re selling experiences because products, as such, are simply too vulgar. Electricity, meanwhile, is no more epiphanic than plumbing, which makes light switches and power outlets the functional equivalents of toilets.

Yet here we find ourselves in a showroom crowded with a glorious tumult of switches and plugs and lightbulbs and cords, the objects and the typology made visible, even huge. The question, then, is why?

What APRDELESP aims to do—spatially, materially and above all methodologically—is to question and deconstruct received hierarchies. Architects should resist their more despotic impulses, should welcome every potential collaboration. They should only design themselves what they absolutely need to design themselves. They should treat every object in a space as equal, even the ones over which they exercise no control. The concrete fact of a building does no more (and often much less) to determine the way we experience it than carpets and plugs, chairs and tchotchkes. Why not start there, APRDELESP wants to ask? Why not design a building around a sofa or a shelf—or, for that matter, a light switch? Which is really more permanent, in the end, the vase that follows you from home to home, that passes from generation to generation, or the house that remains in place, accommodating itself to lives it was never built to contain?

These questions and the thought experiments they generate, can get knotty, even comically abstract. In conversation, the architects behind APRDELESP will talk passionately about ‘space-object-persons’ like the sala-jardín-bar they presented at Lodos gallery in 2021. It is, they wrote in the gallery text, “not a space with objectual qualities, nor an object with spatial qualities. Neither does it find itself casually in the intersection of object and space, but is deeply committed to its existence as both space and object.” (It’s a table.) “The way we define objects determines how we interact with them,” one of the architects might tell you. “It’s a strategy of alienation,” the other might say. “If I tell you a table is a notebook,” he’ll go on, “what happens?” If the table is self-evidently table-y, I will put my beer down on its horizontal surface and pull out my notebook.

But with Accesorios Espaciales, APRDELESP moves beyond semantic provocation—a valuable game in itself—into something more concrete, which is, perhaps, why these objects belong in a gallery dedicated to design rather than art. (The fact that they made this exhibition with a gallery is obviously relevant here; Ago Projects is not just a site or a showroom but an active participant in the process of distilling these concepts into usable objects.) Here, the extension cord/coffee table/light fixture does, in fact, work equally as a lamp and a power outlet and a phone charger and a place to put things. One use does not supersede any other. You tell me this table is a lamp. What do I do? I turn it on.

This is not flexibility in the Modernist mode, which has often involved reducing and reducing and reducing to create empty, elegant multi-use boxes that, as one of the architects puts it, “can permit but not suggest.” APRDELESPprdelesp loves to suggest, prefers a mischievous nudge to a solid pronouncement. They have no interest in the glass box that, as Tati observed, functions as an office building and a tradeshow hall and an airport, not because of any clever programmatic plurality but because of its high-minded vacuity. Modern luxury, fluorescent lit, sold a deeply appealing, deeply calming ideal of efficiency, productivity and aesthetic coherence. It’s a vision that, at least for me, still generates a Kauflust so deep that it makes me uncomfortable. In the 1950s, a Knoll showroom projected you into a fantastic—and, as it turns out, fantastical—future of smooth surfaces and rounded corners and easy living. (Look at the contemporaneous images of the Jetson home in this very catalogue and tell me they don’t evoke an almost narcotic sense of well-being.) Today, that same showroom, filled with the same furnishings, projects you into a past when the future still looked promising. It sold, and continues to sell, a break from chaos.

APRDELESP doesn’t want a break from chaos. The Accesorios Espaciales—the objects themselves, but also the showroom and this catalogue—play with the aesthetic of Modernity. In reality, though, each accesorio is closer to a child’s improvised toy, suggesting uses without circumscribing them. Each one is a stick that might become a sword, a broom, or a bindle, but probably not a surfboard or a stethoscope. The possibilities are mercifully, joyfully finite.

Playtime doesn’t actually end in the nightclub scene with all that malfunctioning technology and stick-on Modernity falling to pieces. In a joyful coda, our characters stumble out of the ruined club as the neon night fades into dawn. Slowly, then suddenly, the four-square grid of traffic that has plagued and thwarted Monsieur Hulot at every turn, resolves into a carousel, giddy and circular and endless.

Not all circles are quite so pleasurable. Today, we romanticize the handmade while also knowing, if we apply even a modicum of rigor, that we will need prefabrication if we want housing and schools and hospitals (not to mention electricity and water) for everyone. Artisanal products will never be universal, at least not if we plan to pay the people who make them anything like a fair wage, yet industrial goods almost invariably implicate us in noxious systems of production and distribution. Around and around we go. It’s infuriating. For early users, the light switch was defined, Isenstadt writes, by “its instantaneity and its amalgam of ignorance and agency.” The instantaneity of contemporary technology has generated the opposite: infinite access to knowledge and devastating paralysis.

But APRDELESP seems to thrive, or at least to live comfortably alongside, these contradictions. They favor the standardized materials typically associated with Modernity—the hook purchased at a hardware store in the Centro Histórico, the folding table leg ordered on Amazon—while exulting in the undifferentiated muchness of the old-school shop windows that Modernists abhorred. (Behrens, I can only imagine, would have railed against APRDELESP’s intervention here in Ago: filling the windows of the showroom with so much stuff that they cease, for all practical purposes, to be windows at all.) They do not, as their Manifesto states, “produce any material specifically for the purpose of sale or exhibition,” yet the Accesorios Espaciales are very deliberately products for sale in a space conceived for exhibitions. It’s a circular way of thinking—not in the sense of flawed, circular logic, but rather thought that turns back on itself to test its own structural integrity, thought for its own sake. “The appropriation is not the future of a project. The project is part of the process of appropriation,” APRDELESP writes in its Manifesto. Making is a carousel, not a labyrinth.

Here, at Ago Projects, they fill the window-walls in a playful Tetris of switches and sockets. There are many colors and many more configurations. It is a visual excess, a gleeful game. With the Accessorios Espaciales they respond to their own prompt not with an answer, per se, but with a deeply thoughtful, eruptive laugh. No one, as Tati well knew, busts up hierarchies like a clown.