Spatial accessories: from the social life of things to the poetics of hardware

Julieta González

It would be a living room about seven meters long by three meters wide. On the left […] there would be a large sofa upholstered in worn black leather, with pale cherrywood bookcases on either side, heaped with books in untidy piles. Above the sofa, a mariner’s chart would fill the whole length of that section of the wall. On the other side of a small low table, and beneath a silk prayer-mat nailed to the wall […] matching the leather curtain, there would be another sofa at right angles to the first […]; it would lead on to a small and spindly piece of furniture, lacquered in dark ref and providing three display shelves for knick-knacks: agates and stone eggs, snuff boxes, candy-boxes, jade ashtrays, a mother-of-pearl oyster shell, a silver fob watch, a cut-glass glass, a crystal pyramid, a miniature in an oval frame. Further on, beyond a padded door, there would be shelving on both sides of the corner, for caskets and for records, beside a closed gramophone of which only four machined-steel knobs would be visible […] A roll-top desk littered with papers and penholders would go with a small cane-seated chair. On a console table there would be a telephone, a leather diary, a writing pad. Then, on the other side of another door, beyond a low square revolving bookcase supporting a large cylindrical vase […] set beneath an oblong mirror in a mahogany frame, there would be a narrow table with its two benches upholstered in tartan, which would bring the eye back to the leather curtain.

Georges Perec, Things: A Story of the Sixties

Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa has declared that the door handle is the ‘handshake of the building’; is the light switch the equivalent for the room? Pallasmaa noted that touch is a key part of remembering and understanding, that ‘tactile sense connects us with time and tradition’. When you touch a light switch, you are sensing the presence of others. You are also touching infrastructure, the network of cables twisting out from our houses, from the writhing wires under our fingertips to the thicker cables, like limbs, out into the countryside, into the National Grid.

Dan Hill, What Happened to the Light Switch, https://designmuseum.org/exhibitions/home-futures/the-light-switch\#

For Georges Perec, an inventory of objects could constitute the subject and backbone for a short story or even a novel. In his writings, notably Species of Spaces (1974), Things: A Story of the Sixties (1965) and Life a User’s Manual (1978), objects, especially domestic ones, are generators of spaces, actions and narratives. In Species of Spaces, Perec sketches out “a project for a novel” (Life a User’s Manual) as an experiment that, inspired by a Saul Steinberg drawing of a building without a façade, “restricts itself to describing the rooms thus unveiled and the activities unfolding in them” and then proceeds to enumerate the objects and the persons within the building that would structure the novel. The novel itself abounds in these detailed descriptions of objects and their occupation of space, a literary stratagem exemplary of Oulipian literary experiments, that he had masterfully deployed in his short novel Things…1

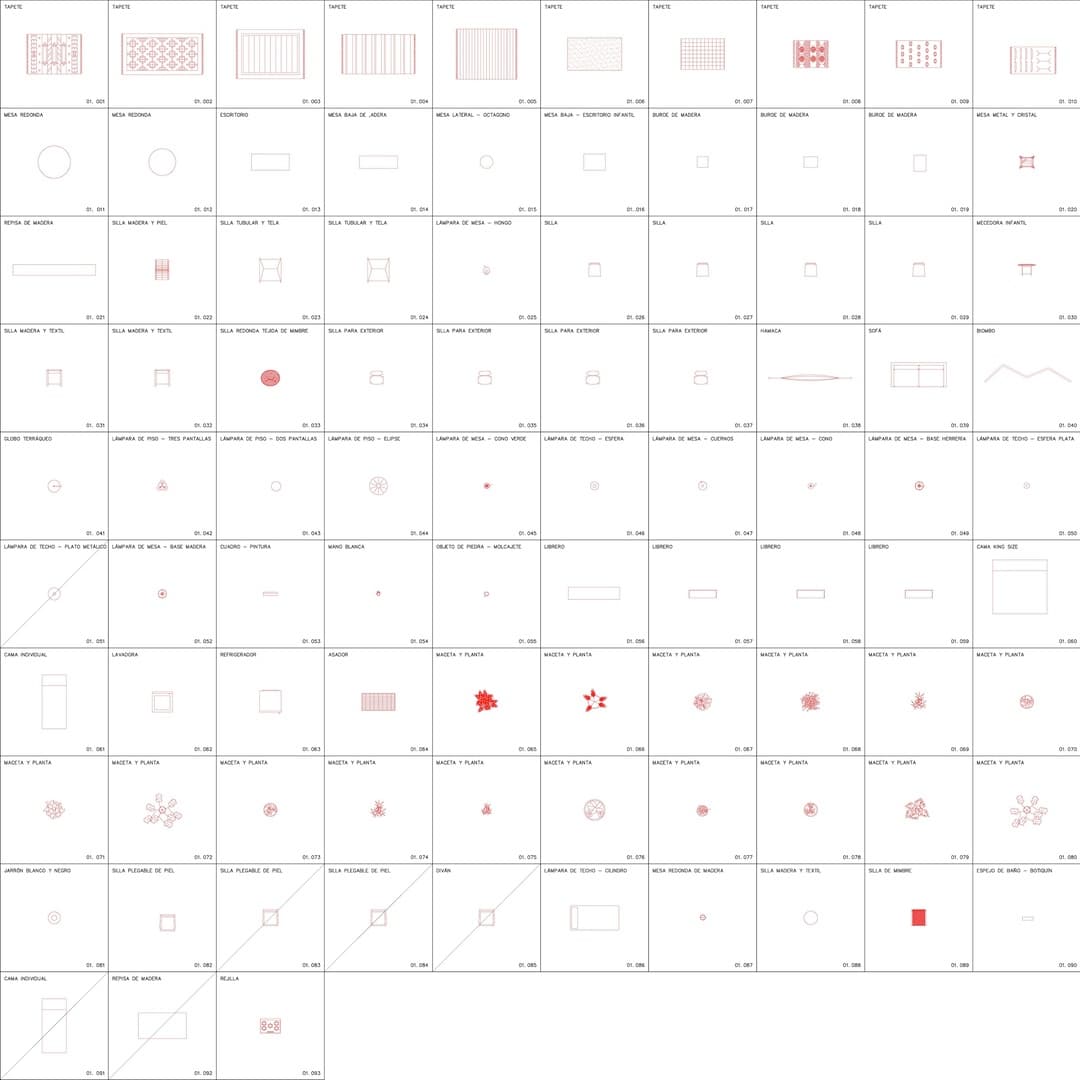

In a similar way, the inventory of objects that will occupy a space is the backbone of APRDELESP’s design methodology. If something distinguishes APRDELESP’s practice as architects and designers, it is their focus on the everyday object and the acknowledgement of its generative potential. In their manifesto on the appropriation of space they state that “constructions are not empty containers waiting for their inhabitants, but rather arrangements composed by a great variety of objects that are constantly changing.” In fact, in the projects they have undertaken to date they seek to make an inventory of the objects belonging to the owners of the spaces they are intervening and to understand how those objects will occupy and shape the space.2 In keeping with their manifesto, they also define the final presentations of the renovated or newly built space, occupied by the inventoried objects, as appropriations. For APRDELESP a chair is just as important as a wall, and they seek to convey this vision to the prospective owners or inhabitants of these spaces so that they can also understand how the different objects organize the space.

Preexisting space survey (belongings inventory) of Case Study 01, 2012 ©️ APRDELESP Archive.

Within this universe of everyday objects, Monobloc chairs, industrial paint buckets, light switches, plastic stools, electrical outlets, working lamps, electrical extensions occupy a special place in their methodology and research. In fact, their most recent project, Accesorios Espaciales (Spatial Accessories), casts the spotlight on the humble light switch, an often taken-for-granted element of interior and exterior lighting systems. Beyond the centrality of objects to their architectural design practice, APRDELESP has undertaken an analysis and exploration of peripheral and /or overlooked utilitarian and decorative objects that while essential and sometimes even iconic do not occupy a central place in the history of design. APRDELESP brings these objects into the conversation and combines them in unexpected ways to produce hybrid architectural and design forms that question the nature of the spaces we live in today and how these objects also play a role in mediating human relations.

In 1929, writing about the Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau (1925), Le Corbusier proposed to substitute the word mobilier for équipement, a gesture that was to change the relations between furniture and architecture and to introduce a technical and functional inflection in the design of household furnishings that would distance them from the decorative imperatives that had prevailed in the past, and that for him “stood for fossilizing traditions and limited utilization.”3 In keeping with his conception of the house as a “machine for living in,” Le Corbusier contended that the term equipment implied the “logical classification of the various elements necessary to run a house that results from their practical analysis.”4 It is possible to understand equipment as not only encompassing furniture but also appliances, built-in cabinetry and partitions, and also including hardware and functional accessories.

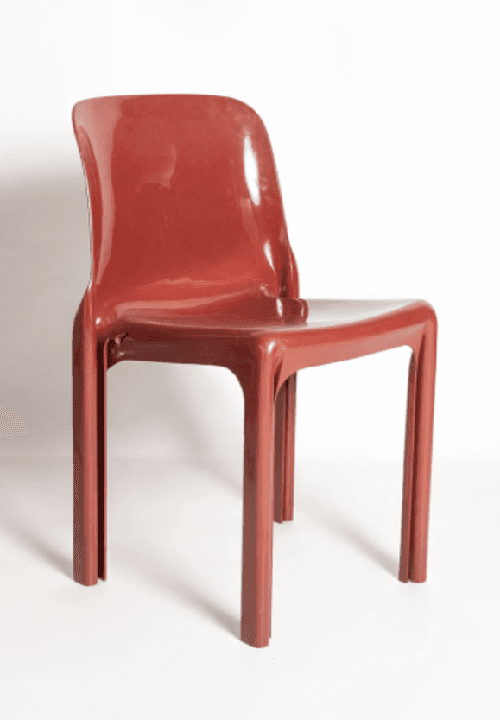

The ethos of equipment and its role in the organization of domestic space proposed by Le Corbusier and furthered by Charlotte Perriand, who had worked with both Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret to design the LC system, was indeed a revolution that was instrumental in the refashioning of industrial design in the following decades. Moreover, the change in materials and forms of production that went hand in hand with the concept of equipment, from wood and the crafts of carpentry and cabinetmaking to metal and industrial production, opened new avenues of research and development in the mass production of domestic objects and furniture. Other sets of knowledge and materials would enter the world of equipment and, in fact, dethrone metal in the world of mass-produced furniture. Plastics, an invention of polymer engineers, and the techniques of molding and extrusion could expedite and economize the labor process to massify the production of furniture and construction hardware in unprecedented ways. Architects and designers seized upon the versatility of plastics to produce a wealth of modular and stackable objects and furniture which have become icons of modern and contemporary design: Robin Day’s molded polypropylene chairs of the 1960s, Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper’s plastic modular chairs, Vico Magistretti’s Selene chair (1961–1968), Joe Colombo’s Universale Chair / No. 4867 (1967) and Henry Massonet’s Fauteuil 300 / Monobloc (1972) from which the humble but ubiquitous and polemical monobloc “white plastic chair” is derived.

Polyside Chair by Robin Day (1963), Seggiolino 4999 by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper (1964), Monobloc Chair by Henry Massonnet (1972), Universale Chair by Joe Colombo (1967), Selene Chair by Vico Magistretti (1969), and an anonymous monobloc chair.

We could say that APRDELESP’s approach to furniture, and the way they broker the relationship between objects, built space and people is informed by Le Corbusier’s notion of equipment but also by the phenomenon of mass production and mass design that the plastics revolution inaugurated. On the one hand, aligned with the ethos of equipment, APRDELESP rejects the hierarchical division between built elements and objects/furniture, equally acknowledging the roles they respectively play in the production and organization of space. On the other, and perhaps making Le Corbusier turn in his grave, they embrace the ugliness of these mass-produced plastic objects, bastards of design, that endlessly litter our built environment. APRDELESP often incorporates these objects into their spatial and object designs, such as their sala-jardín-bar, an exhibition at Lodos where their communal furniture designed for social and convivial encounters shared the space with plastic Monobloc stools, or their design for the Mexican Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale (2023) which also featured the Monobloc plastic chair.

From left to right: Appropriation of Case Study 89 (Mexico Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia 2023), 2019 ©️ APRDELESP Archive; sala-jardín-bar, 2021 ©️ APRDELESP Archive; appropriation of Case Study 69 (Temporary Offices of APRDELESP), 2019 ©️ APRDELESP Archive.

As part of their research into these objects (www.aprdelesp.com) APRDELESP identifies the place they occupy in contemporary Mexican vernacular and street culture, learning from the uses these objects are given in ephemeral, informal, and improvised situations. These lessons translate into APRDELESP’s specific use and occupation of space and even into their reading of the term “appropriation” which they employ to convey the use given to spaces once the design and construction process is completed, in a way reflecting the way informal architectures and economies organize objects and spaces to suit their needs, appropriating spaces that were originally not destined for those uses.

Appropriation of the Case Study 29 (LOS EMPALMES), 2014-2016 ©️ APRDELESP Archive.

Their latest research project, Accesorios Espaciales (Spatial Accessories), revisits, expands and elaborates on Le Corbusier and Perriand’s notion of equipment not only in terms of spatiality and design but also in terms of materials and their focus on mass produced objects, expanding the notion of equipment to include hardware. Eschewing the custom designed hardware that characterized the design vocabulary of architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Carlo Scarpa—textured concrete blocks, joints, knobs, handles and other architectural hardware—APRDELESP repurposes mass-produced and low-cost hardware elements to create their designs.5

The series of prototypes for the different models comprising the Accesorios Espaciales line consists of hybrid multifunctional and multichannel objects that combine different types of hardware commonly found in hardware stores, from big chains such as Home Depot or Sodimac to the neighborhood tlapalerías, and incorporating industrial materials such as carbon steel and galvanized steel. Instead of taking as a point of departure a single autonomous piece of furniture, such as a chair or a table, Accesorios Espaciales focuses on the “accessory,” highlighting the architectural hardware (handles, sockets, switches, hooks, hanging rods, knobs) that is more often than not relegated to the boondocks of design. Inverting the equation and rethinking the proportions and design of some of their elements, the hardware not only becomes central but also generates different functions and spaces. The support of a simple light switch suddenly expands to include a plethora of objects and functionalities–hooks, lamps, stands, baskets, plant holders, mirrors, and even candles–thus creating a space or a room in and of itself. In the case of the Accesorio Espacial PL-35 (CO1),6 an entryway, perhaps?

The even lowlier multiplug becomes a design object as it expands and is transformed into a coffee table on wheels which is also a light fixture and a charging station for multiple electronic gadgets,7 or a desk8 or a simple object of beauty9 that neatly sums up its function as lighting and electric power source.

The Accesorios Espaciales are designed to be serially produced and APRDELESP has planned different modular configurations that can accommodate the different models and typologies. For their gallery presentation at AGO Projects, the line of accessories will be shown on display systems and racks that recall those of hardware stores, temporarily transforming the gallery into an ersatz hardware showroom.

Beyond their take on equipment and hardware, APRDELESP’s Spatial Accessories evoke designer Dan Hill’s above quoted description of the light switch and the tactile experience it affords, which connects us not only to the light, and the space of a room but also to the electric grid running behind the walls, under the floors, connecting rooms, houses, buildings and cities. APRDELESP has redesigned this habitually modest appliance into a multifunctional object that also evidences this sense of tactility, connection and network potential. As a general undertaking, it is possible to identify APRDELESP’s Accesorios Espaciales as an attempt to codify the language of ready-made hardware into a grammar or a poetics of equipment for the 21st century, one hundred years after Le Corbusier and Charlotte Perriand’s equipment transformed the house and its furniture into machines for living.

Footnotes

-

Oulipo was the acronym for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, a group of writers and mathematicians formed by poet Raymond Queneau and mathematician François Le Lionnais in 1960, which included writers such as Georges Perec, Italo Calvino, Jacques Bens, among others. The group explored the generative potential of sets of constraints in the production of literary works, such as writing without a specific letter, or according to certain variables and even equations. Inventories feature among their generative constraints and are a recurring device in Georges Perec’s works, see https://oulipo.net/fr/contraintes and https://oulipo.net/fr/contraintes/inventaire. ↩

-

These inventories form part of their “preexisting space surveys” and they are as relevant as the physical survey of the space itself. See Case Study 01 https://aprdelesp.com/en/#casos-de-estudio&case-study-01&inventario-de-pertenencias, Case Study 03 https://aprdelesp.com/en/#casos-de-estudio&case-study-03&inventario-de-pertenencias-3, Case Study 69.5 https://aprdelesp.com/en/#casos-de-estudio&case-study-69-aprdelesp-temporary-office&caso-de-estudio-69-5-oficina-temporal-de-aprdelesp-feria-material-vol-8 and Case Study 77 https://aprdelesp.com/en/#casos-de-estudio&case-study-77&inventario-de-pertenencias-26. ↩

-

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, Oeuvre Complète, 1910-1929, published by Willy Boesiger and Oscar Stonorov, introduction and texts by Le Corbusier (Paris: Les Editions d’Architecture, 1929), 104 ↩

-

Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, Oeuvre Complète, 1910-1929. ↩

-

In Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001), Kenneth Frampton analyses the significance of architectural hardware in Frank Lloyd Wright’s “text-tile tectonic” and Carlo Scarpa’s “adoration of the joint,” carving a space for hardware in tectonic culture. ↩

-

See model Accesorio Espacial PL-35 (CO1). ↩

-

See model Accesorio Espacial EX-02 (CO1). ↩

-

See model Accesorio Espacial EX-07 (CO1). ↩

-

See model Accesorio Espacial EX-01 (CO1). ↩