Spies, Bankers, and Officials: Notes for a History of the Electrical Products Industry in Mexico

Camilo Ruiz Tassinari

Three-quarters of a century ago, the electrical manufacturing industry represented the last gasp of technological modernity. Worldwide, this industry was a true oligopoly, dominated by a handful of companies that we still know today: General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, Siemens, and Alstom, which was joined shortly after by a couple of Japanese competitors. Mexico was a privileged ground for the international expansion of these companies, and Mexican elites sought to link up with that industry to modernize our country’s economy.

Although our country never had a large company of this type, Mexico was an early consumer and producer of electrical goods. General Electric opened its first importing office in 1896, but more significantly, in 1929 the company founded by Thomas Alva Edison opened a light bulb factory in Monterrey to supply the national demand. The first household appliances arrived in Mexico City and other large Mexican cities very soon after they became popular in the United States, but it was not until the early 1950s that they began to become common—that is, common among the urban upper classes. Two processes enabled this: on the one hand, the electric power generation industry, which had been in crisis due to lack of investment during the 1930s and 1940s, stabilized after a huge infrastructure expansion project started in 1948. Blackouts and brownouts became more infrequent, at least in the Valley of Mexico. Secondly, the large North American companies, GE and Westinghouse, opened their respective modern factories in Mexico to supply the national public at more affordable prices.

Advertisement by General Electric of Mexico, S.A. in the Electricidad de México magazine published by CFE.

If the first wave of industrialization in Mexico took place after 1880 and concentrated on textiles, food processing and, to a lesser extent, steel, by the end of the 1940s a new industrializing wave, broader and focused on other branches, spread throughout the country. The electrical goods industry was one of the main branches of this new post-war industrial revolution. The two central players were General Electric and Westinghouse. These two U.S. corporations both opened factories in Mexico: GE in Ecatepec in 1946 and Westinghouse in Tlalnepantla in 1944, building what was possibly the largest modern factory in the country in terms of capital investment.1

Why would these U.S. corporations want to open large factories in Mexico? Actually, General Electric and Westinghouse represent very different business models. GE opened a modern, but medium-sized factory. The plant was a subsidiary of the U.S. corporation and had a very close relationship with the parent company. Many Mexican employees, not only the top engineers but also intermediate technicians, were sent to the large factory built by Thomas A. Edison in Schenectady, Texas. Edison in Schenectady, New York, so that they could learn about this engineering marvel and become familiar with the production processes and later apply them in Ecatepec. We have here a truly institutional and corporate model of business globalization, where the GE seeks to replicate its way of doing things, and its business culture, and conceives its Mexican factory as an extension of its U.S. facilities. In Mexico, it initially produced a relatively small range of items: light bulbs, washing machines, refrigerators, and basic electrical items.

Westinghouse’s project in Mexico was very different and more representative of the type of alliances that most foreign companies made with Mexican players during the next quarter century, the so-called economic miracle that turned our country into one of the most industrialized societies in the third world. In reality, Westinghouse did not invest in the Tlalnepantla factory nor did it own shares in the Mexican company Industrias Eléctricas de México, S.A. (IEM). Actually, a group of executives, shareholders and bankers linked to Westinghouse in the United States allied themselves with Mexican businessmen and high-ranking officials to form IEM, and to obtain the patent license from the American company. In other words, IEM had a monopoly on the manufacture of Westinghouse products, from which it also bought the components necessary to manufacture electrical products. In this way, Westinghouse did not actually invest a single peso in Mexico, but it ensured a constant flow of sales by exporting different components that were then assembled in Tlalnepantla. IEM was an assembly plant, but that does not mean that it was not a large factory or that it was not technologically advanced.2

Once these two factories were installed, the Mexican government issued a decree that considerably raised import tariffs on finished electrical products. Thus, the European competitors of the two large U.S. corporations would be at a disadvantage as long as they did not open assembly and manufacturing plants in Mexico themselves; this, despite the fact that some imported products were cheaper than those of General Electric and Westinghouse produced in Mexico.

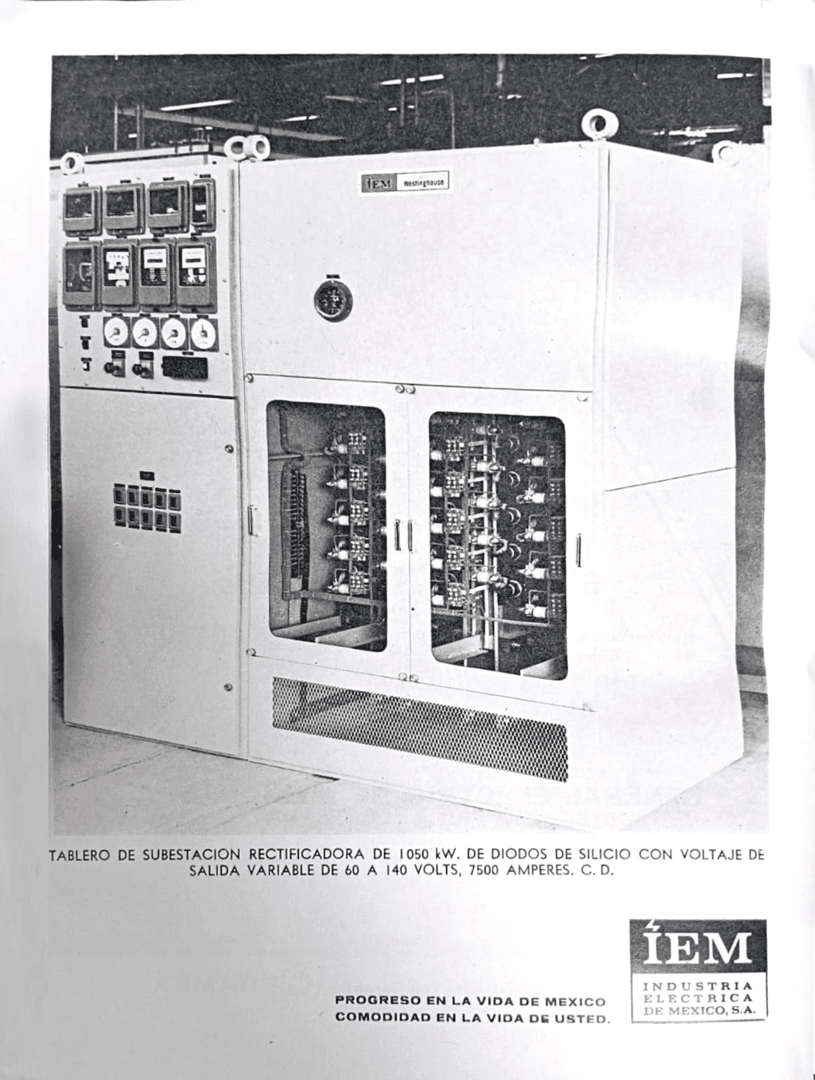

In contrast to General Electric, IEM produced a very wide range of items, including, of course, light bulbs, outlets, washing machines, and refrigerators, but also intermediate capital goods for the electrical industry, such as current transformers, switches, disconnectors, fuses, small generators, etc. IEM never produced the large generators for hydroelectric or thermoelectric plants that Mexico imported from Westinghouse in the United States or its competitors, expensive capital goods, technically very complex and difficult to mass-produce, but it did produce the range of items that one finds in an electrical substation—which is no small thing.

Advertisement by IEM in the Electricidad de México magazine published by CFE.

Opening the factory in Tlalnepantla involved an investment of 75 million dollars, a veritable fortune for the time. But if Westinghouse did not invest in the Tlalnepantla company, who did? One of the main promoters and investors was William Wiseman, a former British spy for mi5, who headed the British intelligence services in the United States during the First World War. Wiseman was an executive of the large New York investment bank Kuhn, Loeb, and Co. and had a close relationship with Westinghouse. This spy and banker prepared the U.S. side of the plan to open IEM, which included convincing one of Westinghouse's executives to leave his position in the U.S. to move to Mexico to run the company. The firm of Kuhn, Loeb, and Co. and Wiseman personally owned many shares of IEM and, when the company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, they were the sales agents. Now, Westinghouse executives were not happy with this plan. They were very upset, in particular, that IEM “stole” one of their executives, and they were probably uncomfortable with the financial wheeling and dealing of this ex-spy. Thus, although IEM bore the Westinghouse seal, and people in Mexico believed it was an extension of the U.S. company, the executives took it upon themselves to communicate to the international business world that the Mexican company was not a simple subsidiary of the U.S. company.3

Advertisement by IEM Westinghouse in the Electricidad de México magazine published by CFE.

Second, IEM was driven by Banamex and the Legorreta family, the main shareholders of that bank. Certainly, Banamex or the Legorretas individually kept a considerable portion of the shares for themselves, but we know that their main activity was to “float” the IEM shares (i.e., sell them) in the Mexican stock market. In this type of transaction, if a bank was involved from the beginning in the organization of a company, and by doing so gave it prestige, credit, and contacts, the bank could normally acquire for itself shares at a reduced price. Thus, if, say, the shares were valued at 100 pesos, at the time of sale the bank would get a commission of 10 pesos, but it could also choose to buy the shares at, say, 70 pesos and sell them in the future if it wished at a higher profit. Of course, this implied a close relationship with the company, a confidence in its future success. Banamex thus became IEM’s Mexican banker and made short and medium-term loans to the company.

The third actor involved in the Westinghouse Mexico scheme was Nacional Financiera (Nafin), the Mexican state development bank. Nafin was one of the central institutions in Mexico’s industrialization: it bought shares, lent money, placed bonds, managed imports and exports, paid for research and development projects, etc. But there was a problem: although Nafin grew a lot in the period 1945–1950, its funds were limited. It had to choose carefully where to put its resources: the country’s industrialization needs were manifold, but it could only afford to support a few projects in depth. Nafin was intimately involved in the IEM project from the beginning and took an important part of the shareholding package.4 It probably did so on similar terms to Banamex: it bought shares when they were cheap, before they went to market, and hoped to be able to sell some in the future when the company’s success would multiply their price. Or not: as a public bank in charge of promoting industrial development, Nafin had different objectives than private banks and could choose to keep a large part of the shareholding if it believed that this was better for the company and for the overall health of the electrical products sector.

So IEM, which had just started production, was listed on the New York and Mexican stock exchanges and had the support of the State’s large industrial bank, the large Mexican commercial bank, and a prestigious investment banking firm on Wall Street. Of course, there were very few Mexican companies with such ties, but the most important thing is that this was the first time that a Mexican company had started in this way, with a large transnational operation, listed on different stock exchanges, etcetera.

However, IEM was not as successful as expected. Although there was a market for electrical products, there were two obstacles. On the one hand, precisely in the first two years that the factory began production, there was a terrible drought that left the hydroelectric dams without water and caused the flow of electric energy to be rationed. The government did everything possible to avoid sudden blackouts. Power in businesses and homes was limited to very low levels, and in industry, electricity use “shifts” were scheduled. In some places, neon lights were banned because they use more energy, and the same happened with some household appliances. What a paradox! On the one hand, the government and companies encouraged the production and purchase of electrical products, as a symbol of modernity, only to immediately limit or prohibit the use of these products because there was not enough electricity.

Secondly, it is possible that this huge factory was conceived on an overly ambitious scale. The large investment did not match the purchasing capacity of the Mexican market. Although we do not know how many product sales it had, we do know that its shares, both on the Mexican and New York stock exchanges, did not sell well. The company was in perennial financial trouble and operated with very low production capacity. The main party affected by this disappointing performance was Nacional Financiera, which had the largest shareholding. But Banamex and Kuhn, Loeb, and Co. were also left with shares that they could not sell at the price they wanted.5

However, IEM was too big and supported by too powerful institutions to let it fall. The attempt to keep it afloat is a fascinating window into how much these companies depended on state protection, and how regulated and politicized these markets were. In those years, as we have said, the Mexican government and electric utilities embarked on a huge infrastructural expansion project, largely financed by the World Bank and Nacional Financiera. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the huge Valle de Bravo dam was built, the Necaxa dam was expanded and the largest thermoelectric plant in Latin America was erected in Tultitlán. The Comisión Federal de Electricidad (cfe) and Luz y Fuerza del Centro were the main agents of this great electrical development. These works cost hundreds of millions of pesos at the time and were possibly the largest infrastructure projects carried out by the Mexican government. Since IEM produced not only household appliances but also intermediate capital goods, its directors made an enormous effort to insert itself into the electrical products market stimulated by the cfe and Luz y Fuerza projects.

In principle, IEM was prohibited from participating as a supplier of these projects. Why? About half of the money had been lent by the World Bank, and it was a rule of this institution that its funds were only to be used to buy capital goods abroad that had to be paid for in dollars, pounds, or francs. In this way, the lack of hard currency in a country like Mexico was alleviated, and the peso was protected: since Mexico had few dollars, these would be provided by the World Bank to buy large generators, turbines, etc. from Siemens or General Electric. Of course, this did not mean that a large part of the construction costs of the projects would inevitably have to be paid in pesos, and to Mexican companies. But those costs would have to be financed by Nafin or the power companies. The World Bank simply asked that the dollars it lent not be used for this current expenditure, but for goods purchased in foreign currencies.

Executives of IEM and the banks that supported it embarked on a campaign to change World Bank rules to allow their dollars to be used for large contracts to supply their company’s products. To begin with, the Mexican Congress passed a law that increased tariffs fivefold on the type of electrical products that IEM wanted to sell. They succeeded in pressuring the directors of Luz y Fuerza and the Federal Electricity Commission to sign purchase orders for hundreds of transformers for seven million dollars, a fortune for the time!6 At first, the World Bank was adamant: its money could only be used to buy products abroad, so the transformer order to IEM would not be financed with its resources. Besides, they had not held an international tender, and cheaper transformers could have been found in Germany or England. But Legorreta, William Wiseman and even the director of Nafinsa, Antonio Carrillo Flores, visited or wrote to the President of the World Bank to ask him to reconsider and make an exception. The latter realized that, beyond the operating rules of his institution, he was facing a real united front of the most powerful economic interests in Mexico, and although the Bank could adhere to the letter of the law, it was not in its interest to provoke the bad faith of those institutions. So, in the interest of keeping harmony, it made an exception, and the World Bank let the seven-million-dollar supply order for IEM go through. After all, the losers were the Mexicans, since the loan money would “yield” less if used in this way.7

Protected and pampered by the state, IEM survived the difficult early years and consolidated its position as the largest electrical products company in the country, with General Electric a close second. With a delay of a few years after the initial turbulence, and once the various forms of electricity consumption rationing were eliminated during the 1950s, most of the electrical products used in Mexican homes were produced by these companies.

The Mexican subsidiaries of General Electric and Westinghouse then became the main drivers of the electrification of daily life. They advertised their products as the direct path to modernity. Their propaganda seemed to say to women: that in the purchase of household appliances lies emancipation within the home. Vacuum cleaners, toasters, and refrigerators would make it as if modest middle-class families had an army of electric maids. At a time of acute nationalist sentiments, they also found a way to square the circle: they presented themselves as Mexican companies collaborating with the economic development of our country and boasted their factories in the State of Mexico. At the same time, they advertised their American belonging and standards and suggested that the use of their products would make users’ lives like those of families in the suburbs of Los Angeles or Chicago. Behind this aspiration for modernity and the comfortable life of the traditional family were not so much the executives in their offices in New York or Polanco, but an unexpected alliance of ex-spies, bankers, and civil servants, united around a great project financed and protected by the Mexican State.

Footnotes

-

Sanford A. Mosk, Industrial Revolution in Mexico (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950). ↩

-

Madigan Hyland, Market Survey of Electricity Sales and Requirements of the Mexican Light and Power Industry, 1950, Hemeroteca Nacional de México. ↩

-

Daniel Heineman to George Messersmith, May 18, 1950, George Messersmith Papers, University of Delaware Library. ↩

-

“Mexico: IEM Purchases,” June 18, 1952, World Bank Group Archives, file 1695983. ↩

-

“Mexlight: Transformer purchase from Industria Eléctrica de México,” March 29, 1951, World Bank Group Archives, file 1695910. ↩

-

“Loan 24ME – Mexican Light and Power Company, Report on Use Visit,” February 7, 1951, World Bank Group Archives, file 1695910. ↩

-

See the various letters from Legorreta and Wiseman to Eugene Black, World Bank Group Archives, file 1695983. ↩